"Let me try and describe Kigali on April 1994," Nick Hughes, a documentary cameraman with Vivid Features told and attentive audience in Harvard. "A convoy of Belgium paratroopers was going to a Catholic mission to rescue a white expatriate and we tugged along. The convoy made its way through the centre of Kigali and there were a few bodies by the side of the road."

"The convoy turned into a heavily populated residential area and along this 10 mile stretch there were roadblocks about every 100 m manned by the interahamwe," Nick went to vividly describe the gruesome picture. "Every 20 meters was a line of bodies neatly laid out, with blood oozing from fatal head wounds and the situation grew grimmer. Every 5 meters, there was another line of bloodstains where more bodies had been laid out some time before. The blood ran down the side of the road and collected in the gutter, the gutter actually flowed with blood."

He was in Kigali from the start of the genocide and in spite of having filmed other serious conflict situation elsewhere, what he witnessed was unimaginable. Like the victims of the killing, he has been haunted by the grotesque images of the killing and he has attempted to exorcise these demons in an engrossing film that has been well received all over the world.

Like James Cameron in the Titanic, Nick Hughes' 100 Days is a moving story of love and brutality that is based on actual events but told in a fictional way that has allowed them to be more dramatic.

"In August 1994, the genocide was just over but the smell of death was heavy in the air," he recalled the horrors that made him vow to immortalize them on motion picture. Bodies rotting under trees, churches full of more recent horror and from the air, mile upon mile of derelict Tutsi houses, crumbling monuments to the families who had once lived there. Of these were to be the only monuments, I knew that was unbearably sad and terribly wrong. I vowed then, in however, small way; I would ensure the Rwandan genocide should not be forgotten."

And in his story that took five years to make, a local Hutu official is persuaded to begin implementing the government's policy against the Tutsi, which is to completely wipe them out.

When the killing begins, Josette (Cleophas Kabasita), a beautiful young Tutsi girl and her family struggle to survive the killing by taking refuge in a church, supposedly protected by the UN forces.

While this is going on, Josette's brother is hunted down and murdered and her boyfriend rescued by the rebels. But the Hutu Catholic priest betrays Josette's family and only agrees to spare her life if she submits to his nightly violations. by the time she is reunited with her boyfriend, neither of them can face the brutal reality of their situation. She is pregnant and bears the priest's child, which she immediately abandons and this certainly heightens the drama of these ghastly events that changed the lives of many Rwandese and observers like Nick.

The precision with which it was executed was an indicator that it was a well planned massacre and the brutality was preposterous.

"I had covered wars before but that was different, that was Genocide," he recalled. "Two women were pulled out of their house, sat down in a pile of bodies and allowed to beg for their lives for twenty minutes before being clubbed to death. Killing surrounded me. I had my own living room window on Auschwitz. I now know that I had seen evil in majesty."

The subsequent reaction by the international community, the churches, humanitarian agencies and the media was one of betrayal that traumatized him in the same way it had traumatized the victims of the genocide.

"That a betrayal of the survivors and a betrayal of the truth was the norm. In September the killers, fled from their crime and sort refuge, across the border but within the safety of DR Congo. They took with them their families and even whole community where they sort protection as hostages," told his attentive Harvard audience. "The world in the form of the UN, Aid agencies and western governments rose as one with great conviction to help the criminals and their communities. While nothing had been done to discourage these same people from planning or committing genocide."

He added: "I stood on Goma airport just two miles across from the Rwanda border, transport plane after transport plane landed, US soldiers plumbed in water and draped food canisters from airplanes that landed beside the road, highly paid Aid workers most whom had never been to Africa before, poured off executive jets, UN PR personnel stood by satellite up-links, giving moment by moment updates to eager journalists. 2 billion dollars were to be spent on the people who had just committed genocide; much of that money was siphoned off to restart a war that continues to this day. The only planes that landed at Kigali airport were for the evacuation of foreign nationals."

This sense of betrayal forms cornerstone of "the truth of the Rwandan question" that should never be forgotten. It is the underlying thematic concern in the film that has been screened at several international film festivals in Toronto, Milan, Los Angeles, Sithengi and others.

This "truth" has not been wholly captured in the numerous excellent books that were written and documentaries made telling every aspect of the genocide.

"I worked on ones revealing the roles of the government, the rebels, the French, the UN and the Catholic church even children and nuns," he noted. "It would seem that the failing of the main protagonists such as the UN, the aid agencies, the Catholic Church, the French were proven beyond doubt but when I read or listened to general public recounting of the perceptions it seemed the idea of betrayal, the magnitude of the suffering was lost."

It is indisputable that documentaries that carried interviews with survivors told tales of loss and cruelty in a way that no fiction ever could match. However, it is true that they often end up being listened to by a small number of people. Full length feature film has a wide audience and it is these people that he hope will watch in 100 Days.

The Rwandan tragedy continues to draw serious discussion. Early this week, International Development Research Centre launched the book The Media and The Rwanda Genocide Edited by Allan Thompson, which is certainly the latest addition in a growing list of material about the genocide. There are several movies Sometimes In April, Hotel Rwanda and others by Rwandese and foreigners that continue to highlight the issue.

I hope we can continue the debate and find a way forward that something like that never happens again in Africa. What are your thoughts?

Thursday, February 8, 2007

Wednesday, February 7, 2007

GAKAARA WA WANJAU—a prolific man of letters

Ngugi wa Thiongo drew international critical attention to writing in African languages. Gakaara wa Wanjau, who passed in 2001, preceded Ngugi as a writer, editor, publisher, political activist and detainee for the cause of Gikuyu language, literature and culture. We examine the life and times of this Gikuyu literary icon.

Gakaara wa Wanjau was an unrivalled Gikuyu literary icon. He was not only the most prolific Kenyan author, but also probably a unique case in Africa of an author and publisher in an African language whose activity never ceased in the last fifty years.

He started writing in the mid-forties and since then, he has published a large number of booklets about the Gikuyu customs, culture and language as well as Kenyan politics and history. He also published many pieces of short stories and several Gikuyu readers for primary school which have been included on the official school syllabus.

"Gakaara's works are examples of highly independent literary production in that from the very beginning of his career as a writer, he published his own books and since the early sixties, has also printed them with his own press," writes Cristiana Pugliese, a lecturer at the English Department of the University of Zimbabwe, who did extensive research on his work.

Gakaara was born at Gakanduini village, near Tumutumu, in 1921. His father, who was a minister of the Church of Scotland Mission, who belonged to the christened and educated Gikuyu elite ensured that his son was well read also. He sent his son to Alliance High School in 1939, where he was a classmate to three future ministers namely Paul Ngei, Jeremiah Nyaga and the late Ronald Ngala.

In 1940, shortly after the arrival of Carey Francis Gakaara was expelled after he and other students had defied and demonstrated against the new master. In December- the same year, he joined the army as a clerical officer.

After the war, he and a group of friends founded the African Book Writers Limited, which was the first company of writers in Kenya. In 1946, Gakaara published his first narrative. It was a short story called Uhoro wa Ugurani (Marriage Procedures), which sold ten thousand copies and became very popular. He co-authored another popular piece– Riua Ritanathua (Before Sunset), before he ventured into political activism.

In 1948, he moved to Nakuru to work as a clerk for a British firm, where came face to face with the colonial oppression and exploitation. He was shocked by the "virtual slavery to which African workers were subjected" that he wrote a political pamphlet in Kiswahili to denounce the situation.

He wrote Roho ya Kiume na Bidii kwa Mwafrika (The Spirit of Manhood and Perseverance for the African), which marked his entry into political activism. Later on, the piece became the main ground for his detention by the colonial government.

At the beginning of 1951, he moved to Nairobi, which was the centre of militant politics, where he became an activist. He worked as a clerk for a short time before turning to writing and publishing full-time.

His activities in the years immediately preceding the declaration of the State of Emergency was in the then popular vernacular press.

In February 1952, he started publishing his own monthly paper called Waigua Atia? (What's the News). It became popular and he opened his offices in Nairobi. He got involved in the movement and in March 1952, he took his first oath and a second one in September of the year. He dropped his Christian name Jonah and resorted to his Gikuyu names.

Apart from editing his magazine Waigua Atia?, Gakaara was very active as a writer and publisher. In 1951, he re-printed his first work of fiction this time calling it Ngwenda Unjurage (I Want You to Kill Me). The same year, he wrote three short stories Ihu ni Ria U (Who is Responsible for her Pregnancy?), O Kirima Ngagua (To Whatever Destination) and Murata wa Mwene (My Bosom Friend).

He produced his first work of Gikuyu poetry Marebeta Ikumi ma Wendo (Ten Love Poems) and a political pamphlet called Kienyu kia Ngai Kirima-ini gia Tumutumu.

In February 1952, Gakaara Book Service was finally registered and he embarked on publishing numerous pieces of work. His first piece was a Gikuyu translation of his first political pamphlet Roho ya Kiume na Bidii kwa Mwafrika under the title Mageria No mo Mahota (Success Comes with Repeated Effort).

In August 1952, he composed and published a political Creed modelled on the Christian Creed called Witikio wa Gikuyu na Mumbi (The Creed of Gikuyu and Mumbi). It was sold at oathing ceremonies to initiates.

He wrote and published carefully crafted and paraphrased Christian hymns to fuel the independence struggle. He wrote and compiled two books Nyimbo cia Gikuyu na Mumbi (Songs of Gikuyu and Mumbi) and Nyimbo cia Ciana cia Gikuyu na Mumbi (Songs of the Children of Gikuyu and Mumbi).

His political writings led to his arrest on October 20, 1952, when the state of emergency was declared. Gakaara was amongst the first to be picked alongside other nationalist who formed the Kapenguria six.

After he was convicted, he was detained in Kajiado, Manda Island, Tawka detention camps. Later on he was moved to Athi River, Karatina and Hola rehabilitation camps before he was taken to Thaithi village, where he was restricted.

After his restriction was lifted, he moved to Nairobi. “In June 1960,” writes Cristiana in her book The Life and Writings of Gakaara wa Wanjau, “he joined Pio Gama Pinto, George Githii and Joe Kadhi on the staff of the KANU party newspaper in Kiswahili Sauti ya KANU which was championing the release of Kenyatta.”

In 1961 he published a book about the Gikuyu clans and left Sauti ya KANU to work as an independent publisher and writer. In the late sixties he went to live in Karatina, where he set up Gakaara Book Service. It was later on changed to Gakaara Press when he got his own printing press.

Although he did not abandon political and historical writings completely, he turned to fiction writing in the mid-sixties under the Atiriri Series.

In the early seventies, Gakaara went back to the old project of running a monthly magazine after ending the Atiriri Series. He started the monthly Gikuyu na Mumbi (Gikuyu and Mumbi) in tabloid-newspaper format. He ran it for four years. In 1976 he changed the format and started publishing it in paperback format under the title Gikuyu na Mumbi Magazine.

It had articles that tackled different social, economic and political issues but the most popular piece was fictional serialization of the adventures of Kiwai wa Nduuta. The over 40 forty issues that he published constitute the bulk of Gakaara’s literary out put.

In 1980, Ngugi wa Thiong’o who was making his transition to writing in Gikuyu, contacted Gakaara and gave him some of his manuscripts. This began their long association that saw Ngugi assist Gakaara publish his detention diary— Mwandiki wa Mau Mau Ithaamirio-ini (Mau Mau Author in Detention.

His association also saw him the Noma award in 1984 but it also landed him into trouble when he was arrested in April 1986 for alleged association with Mwakenya, a charge he continued to deny.

When he was released, he went back to publishing and writing. He churned books that have not only captured historical development but of local languages. He published other authors keen in fostering the development of their languages such as Luo, Kamba, Meru, Kalenjin and Kiswahili.

Certainly a prolific man of letters and a truly unsung literary giant.

Gakaara wa Wanjau was an unrivalled Gikuyu literary icon. He was not only the most prolific Kenyan author, but also probably a unique case in Africa of an author and publisher in an African language whose activity never ceased in the last fifty years.

He started writing in the mid-forties and since then, he has published a large number of booklets about the Gikuyu customs, culture and language as well as Kenyan politics and history. He also published many pieces of short stories and several Gikuyu readers for primary school which have been included on the official school syllabus.

"Gakaara's works are examples of highly independent literary production in that from the very beginning of his career as a writer, he published his own books and since the early sixties, has also printed them with his own press," writes Cristiana Pugliese, a lecturer at the English Department of the University of Zimbabwe, who did extensive research on his work.

Gakaara was born at Gakanduini village, near Tumutumu, in 1921. His father, who was a minister of the Church of Scotland Mission, who belonged to the christened and educated Gikuyu elite ensured that his son was well read also. He sent his son to Alliance High School in 1939, where he was a classmate to three future ministers namely Paul Ngei, Jeremiah Nyaga and the late Ronald Ngala.

In 1940, shortly after the arrival of Carey Francis Gakaara was expelled after he and other students had defied and demonstrated against the new master. In December- the same year, he joined the army as a clerical officer.

After the war, he and a group of friends founded the African Book Writers Limited, which was the first company of writers in Kenya. In 1946, Gakaara published his first narrative. It was a short story called Uhoro wa Ugurani (Marriage Procedures), which sold ten thousand copies and became very popular. He co-authored another popular piece– Riua Ritanathua (Before Sunset), before he ventured into political activism.

In 1948, he moved to Nakuru to work as a clerk for a British firm, where came face to face with the colonial oppression and exploitation. He was shocked by the "virtual slavery to which African workers were subjected" that he wrote a political pamphlet in Kiswahili to denounce the situation.

He wrote Roho ya Kiume na Bidii kwa Mwafrika (The Spirit of Manhood and Perseverance for the African), which marked his entry into political activism. Later on, the piece became the main ground for his detention by the colonial government.

At the beginning of 1951, he moved to Nairobi, which was the centre of militant politics, where he became an activist. He worked as a clerk for a short time before turning to writing and publishing full-time.

His activities in the years immediately preceding the declaration of the State of Emergency was in the then popular vernacular press.

In February 1952, he started publishing his own monthly paper called Waigua Atia? (What's the News). It became popular and he opened his offices in Nairobi. He got involved in the movement and in March 1952, he took his first oath and a second one in September of the year. He dropped his Christian name Jonah and resorted to his Gikuyu names.

Apart from editing his magazine Waigua Atia?, Gakaara was very active as a writer and publisher. In 1951, he re-printed his first work of fiction this time calling it Ngwenda Unjurage (I Want You to Kill Me). The same year, he wrote three short stories Ihu ni Ria U (Who is Responsible for her Pregnancy?), O Kirima Ngagua (To Whatever Destination) and Murata wa Mwene (My Bosom Friend).

He produced his first work of Gikuyu poetry Marebeta Ikumi ma Wendo (Ten Love Poems) and a political pamphlet called Kienyu kia Ngai Kirima-ini gia Tumutumu.

In February 1952, Gakaara Book Service was finally registered and he embarked on publishing numerous pieces of work. His first piece was a Gikuyu translation of his first political pamphlet Roho ya Kiume na Bidii kwa Mwafrika under the title Mageria No mo Mahota (Success Comes with Repeated Effort).

In August 1952, he composed and published a political Creed modelled on the Christian Creed called Witikio wa Gikuyu na Mumbi (The Creed of Gikuyu and Mumbi). It was sold at oathing ceremonies to initiates.

He wrote and published carefully crafted and paraphrased Christian hymns to fuel the independence struggle. He wrote and compiled two books Nyimbo cia Gikuyu na Mumbi (Songs of Gikuyu and Mumbi) and Nyimbo cia Ciana cia Gikuyu na Mumbi (Songs of the Children of Gikuyu and Mumbi).

His political writings led to his arrest on October 20, 1952, when the state of emergency was declared. Gakaara was amongst the first to be picked alongside other nationalist who formed the Kapenguria six.

After he was convicted, he was detained in Kajiado, Manda Island, Tawka detention camps. Later on he was moved to Athi River, Karatina and Hola rehabilitation camps before he was taken to Thaithi village, where he was restricted.

After his restriction was lifted, he moved to Nairobi. “In June 1960,” writes Cristiana in her book The Life and Writings of Gakaara wa Wanjau, “he joined Pio Gama Pinto, George Githii and Joe Kadhi on the staff of the KANU party newspaper in Kiswahili Sauti ya KANU which was championing the release of Kenyatta.”

In 1961 he published a book about the Gikuyu clans and left Sauti ya KANU to work as an independent publisher and writer. In the late sixties he went to live in Karatina, where he set up Gakaara Book Service. It was later on changed to Gakaara Press when he got his own printing press.

Although he did not abandon political and historical writings completely, he turned to fiction writing in the mid-sixties under the Atiriri Series.

In the early seventies, Gakaara went back to the old project of running a monthly magazine after ending the Atiriri Series. He started the monthly Gikuyu na Mumbi (Gikuyu and Mumbi) in tabloid-newspaper format. He ran it for four years. In 1976 he changed the format and started publishing it in paperback format under the title Gikuyu na Mumbi Magazine.

It had articles that tackled different social, economic and political issues but the most popular piece was fictional serialization of the adventures of Kiwai wa Nduuta. The over 40 forty issues that he published constitute the bulk of Gakaara’s literary out put.

In 1980, Ngugi wa Thiong’o who was making his transition to writing in Gikuyu, contacted Gakaara and gave him some of his manuscripts. This began their long association that saw Ngugi assist Gakaara publish his detention diary— Mwandiki wa Mau Mau Ithaamirio-ini (Mau Mau Author in Detention.

His association also saw him the Noma award in 1984 but it also landed him into trouble when he was arrested in April 1986 for alleged association with Mwakenya, a charge he continued to deny.

When he was released, he went back to publishing and writing. He churned books that have not only captured historical development but of local languages. He published other authors keen in fostering the development of their languages such as Luo, Kamba, Meru, Kalenjin and Kiswahili.

Certainly a prolific man of letters and a truly unsung literary giant.

Thursday, February 1, 2007

Prison Literature in Kenya

Prison Literature-namely novels, short stories, poems or plays - that delve into the horrid conditions and experiences in prison, has increased immensely. It is a global phenomenon whose importance in examining the struggles in the society cannot be ignored.

It would for instance be fallacious and inadequate to study the body that is African Literature without mentioning prison writings and the writers who have been so prolific in prison.

Like any other artistic venture, prison literature is an indicator of the various parameters that govern and shape society. It can on the one hand be closely linked to the democratisation of our society and an indicator that even jail has not and cannot dampen the fury of the pen, on the other hand.

A brief explication of these writings indicates clearly that they can also be used to give an adequate, accurate and comprehensive commentary on the socio-economic, political development of Africa and Kenya for that matter.

They are an important resource in showing where we are coming from and what sorts of fragments are scattered along the political, economical and social path that we have used.

Further scrutiny reveals that the body is complex and can be classified differently. The two major classifications are the traditional ones namely-fiction and non-fiction. The non-fiction is further sub-divided into those that are mainly historical or just a diary of events.

However, whether fictional or non-fictional, these writings capture vividly the horrid and gruesome experiences in the state corridors of silence.

These writings can be traced as far back as colonial days in some countries and have become eminent beacons of many other countries and particularly Kenya's post independence histories.

They generally tell where the continent has come from and reached in its quest for justice, upholding the rule of law and ensuring that the fundamental human rights are respected. Prison writings, whether fictional or non-fictional, have become a major source of a vast body of knowledge that tells the African tale.

Kenya's experience can be traced way back during the British rule that saw many militants Kenyans agitating for self-determination thrown into jail and detention camps.

Graduates of these jails and detention camps captured their experiences on paper and sort of subtly outlined a path that has been followed by subsequent writers. The late J.M. Kariuki was amongst the first Kenyans to capture their horrid experiences in his non-fictional account Mau Mau in Detention way back in 1963.

Others soon followed suit. Gakaara wa Wanjau, an established writer and publisher, who had the misfortune of being imprisoned in both the colonial and independent Kenya, documented his experience in the British corridors of silence in his book, Mwandiki wa Mau Mau Ithamerio-ine (Mau Mau Author in Detention).

Independent Kenya has however produced more and better works of art that are indicative of many things. The doors were opened by Abdulatif Abdullah, the first post-independence Kenyan political prisoner.

Abdulatif was imprisoned by the Kenyatta regime for four years and hard labour after he wrote an article titled Kenya Twendapi (Kenya Where are we Headed), in reaction to the disbandment of K.P.U. while serving his term, he wrote a collection of poems called Sauti ya Dhiki, which ironically won the second the edition of the erstwhile prestigious Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature.

Other writers were later to follow and each chose a unique way to capture the grisly events in jail. The most famous of these writers is Ngugi wa Thiong'o. His activities community theatre in Kamirithu led to his detention in 1977. While in Kamiti, he wrote Detained: A Writer's Prison Diary, which is a diversion from his other fictional works.

Others, who have contributed a great wealth in this body, include Maina wa Kinyatti, Koigi wa Wamwere and Wanyiri Kihoro more recently.

Maina wa Kinyatti perhaps has the highest number of books that vividly describe his harrowing experience. He has a collection of poems A Season of Blood: Poems from Kenyan Prison (1995), his day-in-day-out recollections, Kenya -A Prison Notebook (1996) and a third one that details events covering his arrest, torture and imprisonment called Mother Africa.

Wanyiri Kihoro, the Nyeri Town MP has documented his ordeal in Never Say Die, which another writer, the late Wahome Mutahi described as a brilliant piece of work that was the closest work of art that detailed events that want on at the infamous Nyayo House basement cells.

There are hordes of other works that have been written that are largely fictional. Several others have a thrilling fast-paced drama. The East African Educational Publishers, who have a big collection in this area, have listed them under their Spear series.

Most of these writings that are largely confessions of erstwhile crooks like John Kiriamiti's My Life in Crime, Kiggia Kimani's Prison is Not a Holiday Camp or Charles Githae's Comrade Inmate, amongst other offer scintillating narratives but they are all shrouded by the gruesome prison experience and the grotesque Mutahi's is shocking.

the late Wahome Mutahi's Three Days on the Cross Karuga Wandai's Mayor in Prison and Benjamin Garth Bundeh's Birds of Kamiti are amongst those listed in the spear series in spite of their strong real life experience. Wahome was arrested a few days after he had submitted his manuscript to the publishers and when he was released, the publishers asked him to revise it incorporate other details of his incarceration.

Bundeh's Birds of Kamiti is a detailed account of his close shave with the hangman's noose. It is a personal account that is gripping and quite emotional.

However, these works whether autobiographical or biographical or mere confessions are representative of pertinent issues. They provide a social commentary that needs consideration. They open new insights for both the authors and society at large.

Incarceration did not provide an opportunity for Ngugi to write a prison diary but within this physical prison, Ngugi stumbled upon a non-physical prison, namely language.

Ngugi defied this non-physical prison he had done the physical. He sought the refuge in the power of the pen and wrote Detained. He defied the subordination of-physical prison and found refuge in Gikuyu. In cell 16, he wrote Caitaani Mutharabaine (Devil on the Cross) in Gikuyu as a demonstration of his new found freedom and EAEP boss intimated to me that his latest manuscript is being scrutinised.

For others like Maina wa Kinyatti, "writing and reciting poems in solitary confinement under conditions of unendurable physical and psychological torture hardened the heart and steeled the mind to remain steadfast and truthful to the cause".

Incarceration has not been limited in Kenya only. Apartheid South Africa jailed writers like Dennis Brutus, who wrote Letters to Martha, the late Alex La Guma amongst others.

Jack Mapanje from Malawi, Kofi Awoonor from Ghana, Sherif Hatata and Nawal el Sadaawi from Egypt, and the first African recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Prof. Wole Soyinka have all been there before.

They have also served to help raise fundamental questions on the dispensation of justice and basically the entire process of crime and punishment. The works, whether biographical like Wanyiri's Never Say Die, which was also nominated for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, or confessions by erstwhile bank robbers or other crooks or other real-life drama experiences, have served as clear indicators that system is rotten and closer scrutiny is necessary.

WHAT DRIVES THEM TO WRITE ?

Could it be the appalling, grotesque, grisly conditions in the state corridors of silence that has kept the number of prison writings growing year in year out or just an insatiable desire to write and keep the tabs?

It is certainly this and many other reasons that keeps that pen rolling. A chat with a number of these writers reveals that it is a combination of these and many other things. It is a bottomless pit of stories and the experience cannot be bottled inside. "One normally feels that the story has to be told", comments one writer.

"For many writers", observed the late Wahome Mutahi, who has two books - Three Days on the Cross and Jail Bugs - on prison writing, "Writing about their horrid experiences behind bar is often cathartic". It is a way of telling time to comment on many things that go on both behind bars and outside.

Writing is a way of telling the rest of the world, the horrid conditions that persist in these places that society places some of its members for correction and punishment. It has been described differently by many writers.

It is a place, where like Benjamin Garth Bundeh describes in Birds of Kamiti as a totally new world. "A world of prisoners, of warders, and of the tragic twist of fate. It was a world in which either the spirit was completely broken and degraded, or true courage was born".

"When you enter this place", writes Bundeh, "you have to forget everything about the outside world. The dungeon becomes your home and you must survive smoking is treason here - But we still manage to pass the traffic load of fags and like stone age man, we create fire in these caves". It is a place where the basic instinct of survival reigns supreme.

Writers want to talk about this place where every effort is geared towards removing any trace of humanity that could be remaining to these inmates. Bundeh notes in his non-fictional dossier that after his first night a truer picture started forming.

"I saw more people and most of them looked like creatures out of a nightmare. Together with them, we had ceased to be human beings. Our names had been taken away from us. We had been relegated to more numbers in a heap of files. Both the beginning and end of life seemed to have been lost".

They want to narrate about these correctional places that are a law unto them selves. Into the damp mould and stagnation of these tombs, "the warders would from time to time burst in to remind us that unlike free people", inmates "could be tormented again and again, physically and spiritually, subtly and brutally, collectively and individually, day and night. "The warders enjoyed treating us to the choicest of gutter oaths", notes Bundeh.

The authorities find several ways to further break and degrade the inmates. There is torture that targets the most vulnerable parts of our bodies and every writer seems to have endured this. The occasional beating is often capped with eating partially cooked food and solitary confinement that many writers argue that it is not different from a shot of L.S.D. or any other hallucinogen. They both degrade people "only that the drugs make one mad more quickly thus removing the utter hopeless".

Besides the deplorable and dehumanising conditions behind bar that most writers want to vividly point out, the other issues that often come out in prison literature appeals to the outside prison conditions. These books, whether fictional or non-fictional all offer important questions that society needs to consider for further scrutiny.

In their writings, the writers often want to focus society on the entire system of justice and its dispensation. Many question the whole system of crime and punishment and although some don't ask directly, the effectiveness of the whole set-up is put to test.

Bundeh, who was on the death row and actually witnessed some of his inmates and friends executed packs his narrative with so much energy and emotion that you can feel it deeply and is more direct when he poses these questions.

"I wonder, should any human being be allowed to condemn another human being to death? Should one form of killing be lawful and another one unlawful? Should the law be allowed to take away that which it cannot create? Is there any correlation between the execution of treasonous, murderers or violent robbers and the number of crimes committed? The gallows in Kenya, the guillotine, the electric chair, and firing squads elsewhere - are these deterrents?"

Many books that are non-fictional have a similar trait. The authors are in many instances unwilling guests of the state in their corridors of silence. Most of these authors repeatedly turn to writing as a catharsis. Majority has been thrown behind bars for their political beliefs and in their writings, they have more than once provided new insights into the political machinations of this country.

Karuga Wandai, an erstwhile deputy mayor in Thika, provides interesting insights of the "siasa za kumalizana" in the Kenyan political arena in his prison account "Mayor in Prison". Although it is an account of his survival and fight for his freedom, he nonetheless manages to show the country's struggles, transition and some of the central issues that greatly influenced the political under-dealings.

Wanyiri Kihoro, the erstwhile Nyeri Town MP in his biography Never Say Die or Wahome Mutahi's work of fiction Three Days on the Cross capture the dark days in the country's political spectrum. They vividly document their gruesome ordeal in the hands of the state security machinery in the infamous underground cells of Nyayo houses was an experience that couldn't be bottled inside.

The other way that many authors have managed to give a commentary on the political manoeuvres has been by giving the politicians central parts in the narratives. They (the characters) have in turn revealed how they manipulated people in society and how laws have been turned to suit a few and how these laws are in turn used against them once they fall out of favour.

By Kimani wa Wanjiru.

It would for instance be fallacious and inadequate to study the body that is African Literature without mentioning prison writings and the writers who have been so prolific in prison.

Like any other artistic venture, prison literature is an indicator of the various parameters that govern and shape society. It can on the one hand be closely linked to the democratisation of our society and an indicator that even jail has not and cannot dampen the fury of the pen, on the other hand.

A brief explication of these writings indicates clearly that they can also be used to give an adequate, accurate and comprehensive commentary on the socio-economic, political development of Africa and Kenya for that matter.

They are an important resource in showing where we are coming from and what sorts of fragments are scattered along the political, economical and social path that we have used.

Further scrutiny reveals that the body is complex and can be classified differently. The two major classifications are the traditional ones namely-fiction and non-fiction. The non-fiction is further sub-divided into those that are mainly historical or just a diary of events.

However, whether fictional or non-fictional, these writings capture vividly the horrid and gruesome experiences in the state corridors of silence.

These writings can be traced as far back as colonial days in some countries and have become eminent beacons of many other countries and particularly Kenya's post independence histories.

They generally tell where the continent has come from and reached in its quest for justice, upholding the rule of law and ensuring that the fundamental human rights are respected. Prison writings, whether fictional or non-fictional, have become a major source of a vast body of knowledge that tells the African tale.

Kenya's experience can be traced way back during the British rule that saw many militants Kenyans agitating for self-determination thrown into jail and detention camps.

Graduates of these jails and detention camps captured their experiences on paper and sort of subtly outlined a path that has been followed by subsequent writers. The late J.M. Kariuki was amongst the first Kenyans to capture their horrid experiences in his non-fictional account Mau Mau in Detention way back in 1963.

Others soon followed suit. Gakaara wa Wanjau, an established writer and publisher, who had the misfortune of being imprisoned in both the colonial and independent Kenya, documented his experience in the British corridors of silence in his book, Mwandiki wa Mau Mau Ithamerio-ine (Mau Mau Author in Detention).

Independent Kenya has however produced more and better works of art that are indicative of many things. The doors were opened by Abdulatif Abdullah, the first post-independence Kenyan political prisoner.

Abdulatif was imprisoned by the Kenyatta regime for four years and hard labour after he wrote an article titled Kenya Twendapi (Kenya Where are we Headed), in reaction to the disbandment of K.P.U. while serving his term, he wrote a collection of poems called Sauti ya Dhiki, which ironically won the second the edition of the erstwhile prestigious Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature.

Other writers were later to follow and each chose a unique way to capture the grisly events in jail. The most famous of these writers is Ngugi wa Thiong'o. His activities community theatre in Kamirithu led to his detention in 1977. While in Kamiti, he wrote Detained: A Writer's Prison Diary, which is a diversion from his other fictional works.

Others, who have contributed a great wealth in this body, include Maina wa Kinyatti, Koigi wa Wamwere and Wanyiri Kihoro more recently.

Maina wa Kinyatti perhaps has the highest number of books that vividly describe his harrowing experience. He has a collection of poems A Season of Blood: Poems from Kenyan Prison (1995), his day-in-day-out recollections, Kenya -A Prison Notebook (1996) and a third one that details events covering his arrest, torture and imprisonment called Mother Africa.

Wanyiri Kihoro, the Nyeri Town MP has documented his ordeal in Never Say Die, which another writer, the late Wahome Mutahi described as a brilliant piece of work that was the closest work of art that detailed events that want on at the infamous Nyayo House basement cells.

There are hordes of other works that have been written that are largely fictional. Several others have a thrilling fast-paced drama. The East African Educational Publishers, who have a big collection in this area, have listed them under their Spear series.

Most of these writings that are largely confessions of erstwhile crooks like John Kiriamiti's My Life in Crime, Kiggia Kimani's Prison is Not a Holiday Camp or Charles Githae's Comrade Inmate, amongst other offer scintillating narratives but they are all shrouded by the gruesome prison experience and the grotesque Mutahi's is shocking.

the late Wahome Mutahi's Three Days on the Cross Karuga Wandai's Mayor in Prison and Benjamin Garth Bundeh's Birds of Kamiti are amongst those listed in the spear series in spite of their strong real life experience. Wahome was arrested a few days after he had submitted his manuscript to the publishers and when he was released, the publishers asked him to revise it incorporate other details of his incarceration.

Bundeh's Birds of Kamiti is a detailed account of his close shave with the hangman's noose. It is a personal account that is gripping and quite emotional.

However, these works whether autobiographical or biographical or mere confessions are representative of pertinent issues. They provide a social commentary that needs consideration. They open new insights for both the authors and society at large.

Incarceration did not provide an opportunity for Ngugi to write a prison diary but within this physical prison, Ngugi stumbled upon a non-physical prison, namely language.

Ngugi defied this non-physical prison he had done the physical. He sought the refuge in the power of the pen and wrote Detained. He defied the subordination of-physical prison and found refuge in Gikuyu. In cell 16, he wrote Caitaani Mutharabaine (Devil on the Cross) in Gikuyu as a demonstration of his new found freedom and EAEP boss intimated to me that his latest manuscript is being scrutinised.

For others like Maina wa Kinyatti, "writing and reciting poems in solitary confinement under conditions of unendurable physical and psychological torture hardened the heart and steeled the mind to remain steadfast and truthful to the cause".

Incarceration has not been limited in Kenya only. Apartheid South Africa jailed writers like Dennis Brutus, who wrote Letters to Martha, the late Alex La Guma amongst others.

Jack Mapanje from Malawi, Kofi Awoonor from Ghana, Sherif Hatata and Nawal el Sadaawi from Egypt, and the first African recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Prof. Wole Soyinka have all been there before.

They have also served to help raise fundamental questions on the dispensation of justice and basically the entire process of crime and punishment. The works, whether biographical like Wanyiri's Never Say Die, which was also nominated for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, or confessions by erstwhile bank robbers or other crooks or other real-life drama experiences, have served as clear indicators that system is rotten and closer scrutiny is necessary.

WHAT DRIVES THEM TO WRITE ?

Could it be the appalling, grotesque, grisly conditions in the state corridors of silence that has kept the number of prison writings growing year in year out or just an insatiable desire to write and keep the tabs?

It is certainly this and many other reasons that keeps that pen rolling. A chat with a number of these writers reveals that it is a combination of these and many other things. It is a bottomless pit of stories and the experience cannot be bottled inside. "One normally feels that the story has to be told", comments one writer.

"For many writers", observed the late Wahome Mutahi, who has two books - Three Days on the Cross and Jail Bugs - on prison writing, "Writing about their horrid experiences behind bar is often cathartic". It is a way of telling time to comment on many things that go on both behind bars and outside.

Writing is a way of telling the rest of the world, the horrid conditions that persist in these places that society places some of its members for correction and punishment. It has been described differently by many writers.

It is a place, where like Benjamin Garth Bundeh describes in Birds of Kamiti as a totally new world. "A world of prisoners, of warders, and of the tragic twist of fate. It was a world in which either the spirit was completely broken and degraded, or true courage was born".

"When you enter this place", writes Bundeh, "you have to forget everything about the outside world. The dungeon becomes your home and you must survive smoking is treason here - But we still manage to pass the traffic load of fags and like stone age man, we create fire in these caves". It is a place where the basic instinct of survival reigns supreme.

Writers want to talk about this place where every effort is geared towards removing any trace of humanity that could be remaining to these inmates. Bundeh notes in his non-fictional dossier that after his first night a truer picture started forming.

"I saw more people and most of them looked like creatures out of a nightmare. Together with them, we had ceased to be human beings. Our names had been taken away from us. We had been relegated to more numbers in a heap of files. Both the beginning and end of life seemed to have been lost".

They want to narrate about these correctional places that are a law unto them selves. Into the damp mould and stagnation of these tombs, "the warders would from time to time burst in to remind us that unlike free people", inmates "could be tormented again and again, physically and spiritually, subtly and brutally, collectively and individually, day and night. "The warders enjoyed treating us to the choicest of gutter oaths", notes Bundeh.

The authorities find several ways to further break and degrade the inmates. There is torture that targets the most vulnerable parts of our bodies and every writer seems to have endured this. The occasional beating is often capped with eating partially cooked food and solitary confinement that many writers argue that it is not different from a shot of L.S.D. or any other hallucinogen. They both degrade people "only that the drugs make one mad more quickly thus removing the utter hopeless".

Besides the deplorable and dehumanising conditions behind bar that most writers want to vividly point out, the other issues that often come out in prison literature appeals to the outside prison conditions. These books, whether fictional or non-fictional all offer important questions that society needs to consider for further scrutiny.

In their writings, the writers often want to focus society on the entire system of justice and its dispensation. Many question the whole system of crime and punishment and although some don't ask directly, the effectiveness of the whole set-up is put to test.

Bundeh, who was on the death row and actually witnessed some of his inmates and friends executed packs his narrative with so much energy and emotion that you can feel it deeply and is more direct when he poses these questions.

"I wonder, should any human being be allowed to condemn another human being to death? Should one form of killing be lawful and another one unlawful? Should the law be allowed to take away that which it cannot create? Is there any correlation between the execution of treasonous, murderers or violent robbers and the number of crimes committed? The gallows in Kenya, the guillotine, the electric chair, and firing squads elsewhere - are these deterrents?"

Many books that are non-fictional have a similar trait. The authors are in many instances unwilling guests of the state in their corridors of silence. Most of these authors repeatedly turn to writing as a catharsis. Majority has been thrown behind bars for their political beliefs and in their writings, they have more than once provided new insights into the political machinations of this country.

Karuga Wandai, an erstwhile deputy mayor in Thika, provides interesting insights of the "siasa za kumalizana" in the Kenyan political arena in his prison account "Mayor in Prison". Although it is an account of his survival and fight for his freedom, he nonetheless manages to show the country's struggles, transition and some of the central issues that greatly influenced the political under-dealings.

Wanyiri Kihoro, the erstwhile Nyeri Town MP in his biography Never Say Die or Wahome Mutahi's work of fiction Three Days on the Cross capture the dark days in the country's political spectrum. They vividly document their gruesome ordeal in the hands of the state security machinery in the infamous underground cells of Nyayo houses was an experience that couldn't be bottled inside.

The other way that many authors have managed to give a commentary on the political manoeuvres has been by giving the politicians central parts in the narratives. They (the characters) have in turn revealed how they manipulated people in society and how laws have been turned to suit a few and how these laws are in turn used against them once they fall out of favour.

By Kimani wa Wanjiru.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Parading for Peace by Bel Haj Taib from Tunisia

An eye-catching work or art. A fragile multi-media piece, Bel Haj’s sculpture/installation dubbed “Parading for Peace” composed of several tortoises made from soldiers helmets and in a symbolic and yet contradictory postures that leaves you with no doubt that it is a military parade hopefully for piece.

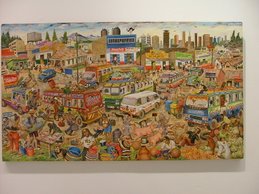

The Market by Bertiers from Kenya

It is always a beehive of activities and no one can aptly capture like an artists does. It is a deep, profound piece with various stories that have many related subthemes that make Bertiers such an outstanding artist of his generation.

Ariel Landscape by Bruce Onobrakpeya from Nigeria

Made from various computer CPU parts, the piece leaves you with no doubt as to what you may be looking. An aerial view of a well planned city and you can actually pick out where the industrial area is located, the residential estates, skyscrapers and others.